Studying the science of a potential crime scene

Students have been smashing skull models to study forensic evidence of a hypothetical “crime.”

Picture this: Students walk in to their engineering class, where they are learning how to build a lifelike skull, fit it with (realistic) synthetic skin, fill it with an artificial “brain,” all so that they can smash it to smithereens.

Why? Well, it might help if you’ve seen any of the “CSI” television shows or if you know anything about forensic science.

“[It’s all] to give an accurate depiction and practical application of what a real crime scene may look like, and how forensics teams analyze evidence used to solve crimes,” science teacher Jonathan Kiniry said.

The AMSA science department this year began offering high school students research opportunities in various fields. In December, five students in teacher Jeremy Morris’ engineering class worked diligently to create a new lab for forensics.

Their aim was to use computer software to design skulls, which are then smashed to see where the blood splatters from inside of the head onto a surface from varying angles, heights, and with the use of different weapons.

It was a project that AMSA has never seen the likes of before.

“We are testing the effects of blunt-force trauma on the skull,” said senior Joey Palmieri, adding that it will allow students to get unique and one-off research findings on how much force is needed to—well, there is no really nice way of saying it—destroy a person’s skull.

Students working in engineering have a variety of tools that they can use to enhance their learning, including a three-dimensional printer.

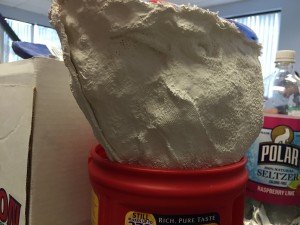

“Currently we have been using Solidworks to design a mold for the skull, and [recently] we used plaster to make a mold for the brain,” Joey said.

Joey also mentioned that the engineering class in conjunction with the science department plans to 3D-print it using realistic bone material. The process utilizes a special printer that uses an inkjet that melts plastic, allowing it to be easily manipulated and “printed” into another shape, allowing for infinite possibilities.

“It is the start of a cross-curricular spirit,” he explained, and noted that in future years AMSA might even be able to get better synthetic skin to make even more biological experiments possible.

Students worked with plaster to make skull models, which were later smashed and studied.

Synthetic skin is widely used to treat burn victims, but it can also be used to study how skin reacts to rigorous “wear and tear” as well as to test just how strong skin is and what its limits are in terms of physical abuse.

As an added benefit, students are learning how collaboration can create a positive working environment that promotes innovation. In theory, it should motivate them to learn and explore other ways to collaborate with their peers to make for a better AMSA learning environment.

“It takes more than one person to make something creatively,” Mr. Kiniry said. “It’s not easy to just throw a lab together. It takes time and commitment.”

Even in its early stages, the program seems to have motivated students to collaborate and to benefit from that teamwork.

“Figuring out exactly how we wanted to execute the steps of the project, there was no set way to do it when we started, so we had to start the process all by ourselves,” senior Mike Shulman said.

Students ended up making molds out of Gel-10 silicone, which is a relatively expensive material ranging from $50 to $60 for two gallons of solution.

Mike explained that the plaster used to make the actual skulls is cheap, making the project a viable solution for many high schools, so the only expensive material is the Gel-10 silicone.

Working with a small group of about five people was a good fit, Mike said, because “tasks could be delegated to each person and everyone is making an effort to work and make this project successful.”

The group is currently waiting to receive dental impression materials to make the skulls even more realistic, so the project is currently on hold. But Mike says that he is optimistic that it will be completed before the end of school in June.

Even though the project has yet to be completed, just hearing students describe it so excitedly shows that AMSA might be on to something valuable in terms of ways to motivate students and enhance their learning with real-world experiences.

“The biggest setback has been waiting for materials to arrive, but we cannot say for sure about the success of the project until we complete it,” Mr. Morris said.

In any case, much of the evidence is in—even if there is more smashing to be done.

Sam Stiller is a senior at AMSA. He enjoys writing about what truly affects the everyday life of his peers. Sam is the editor of the student yearbook,...