Will the gun control discussion ever take place?

More in Opinion

Google image/Creative Commons license

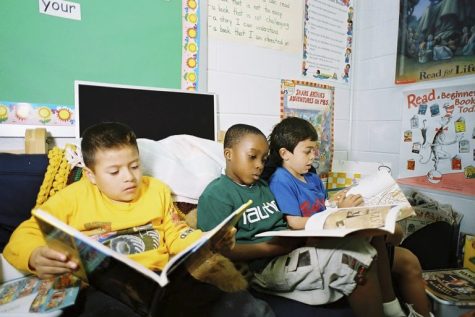

Concert-goers were exposed and vulnerable targets for a shooter in a hotel tower.

It has been more than three months since the deadliest mass shooting in American history, and our country still has not had a focused discussion about gun control.

Shootings and mass attacks have become all too common, sparking an initial outpouring of grief, a call for compassion for the victims, and a plea to table serious discussion until a “more appropriate time.” The time, it seems, never comes.

On Oct. 1, 58 concert-goers in Las Vegas were killed and more than 500 injured by a man who shot multiple high-powered weapons from an adjacent hotel tower. A month later, another shooter massacred 26 worshippers in a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas.

The only reason that discussions have been avoided is because Republican politicians know how to change the conversation. When they feel that their guns are in danger, they talk about anything other than weapons used, how they were obtained, and potential measures that might curb access.

“There will certainly be a time for that policy discussion [gun control] to take place, but that’s not the place that we’re in at this moment,” White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said the day after the Las Vegas incident.

When conservatives do eventually comment, it is mental health, not guns, that becomes the topic of discussion.

When asked about the attack during a visit to Tokyo, President Donald J. Trump told BBC News that the shooting was not “a guns situation” but “a mental health problem at the highest level.”

It has been reported by multiple outlets that Devin Kelley, the Texas church shooter, had a long history of spousal, child, and animal abuse and at one point fled from a mental hospital in which he was being treated. He was given a bad conduct discharge by the Air Force.

Mourners gather at the site of the mass shooting in Las Vegas.

The Air Force has acknowledged that it failed to enter Mr. Kelley’s name into a federal database that would have prevented him from obtaining firearms.

The system is badly in need of an overhaul on multiple levels. Yet gun companies, lobbyists, the National Rifle Association, and politicians consistently avoid any meaningful discussion.

Some gun advocates have actually noted that a citizen shot at Mr. Kelley outside the church, wounding him and hastening his departure, using it as “evidence” that we need more people with guns, not fewer.

Clearly, this is a gun issue, not just a mental health issue. Granted, Mr. Kelley was unstable, but the bigger problem is his ability to purchase a gun considering his mental and emotional state. It does not matter if someone else was able to shoot him — this man should never have had a gun in the first place.

“It is uniquely and tragically American,” Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) was quoted as saying in USA Today. “As long as our nation chooses to flood the country with dangerous weapons and consciously let those fall into the hands of dangerous people, these killings will not abate.”

Mr. Murphy is right in saying this problem is uniquely American. Other countries have taken considerable action toward preventing future gun violence. Australia, for example, enacted strict gun control measures just weeks after the deadly Port Arthur shooting killed 35 in April 1996. The United Kingdom enacted similar legislation in the wake of a school shooting in Dunblane, Scotland, a month before the Port Arthur incident.

Gun violence in those nations is extremely rare today. If we were to follow suit, gun-related violence should naturally decline.

Unfortunately, politicians here are unable and unwilling to search for common ground. Clearly, regulation of the means of massacres — guns — is the most basic and efficient approach, but conservatives fail to realize it.

In the meantime, shootings continue at a horrific pace. We have to ask ourselves a hard question if we ever want to see this issue resolved: How many more people have to die before Congress is willing to do something?

Chris is a senior and has attended AMSA since 6th grade. He joined The AMSA Voice in hopes of getting some writing experience (in any form) under his...