AMSA students find and study soil contamination

EDITOR’S NOTE: Second in a four-part series about AMSA’s innovative science research program

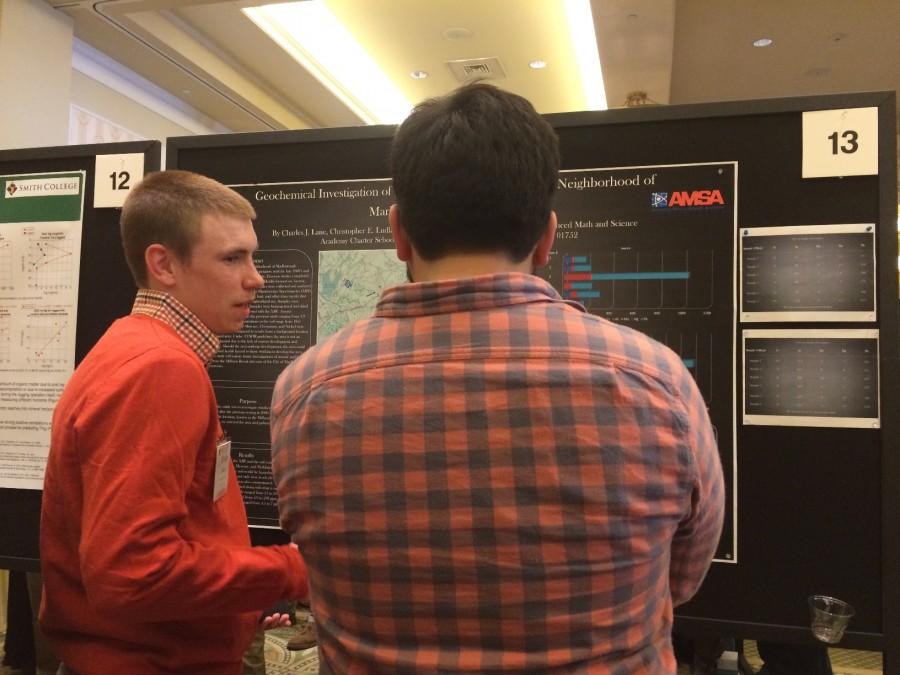

Charlie Lane presented his findings about soil contamination around Milham Brook to the Geological Society of America last month.

Charlie Lane is on his hands and knees at the banks of the Milham Brook in Marlborough digging through the dirt. He collects samples of soil and puts them in plastic bags to check for levels of arsenic, chromium, molybdenum, lead, and mercury.

Later, he uses an X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometer (XRF) to chart the levels that may have resulted from previous agricultural use, namely pesticides.

Anyone watching Charlie work would be forgiven for thinking that he is a scientist. But Charlie is a junior at AMSA.

Charlie is part of a group of AMSA students, taught by earth science teacher Timothy Vaillancourt, conducting geochemical analysis across Marlborough and Hudson as part of the science department’s research program.

Students have found alarming levels of potentially dangerous elements in soil around Marlborough and have presented their findings to the Geological Society of America.

“We’re going to keep investigating the causes of the elevated levels,” senior researcher Chris Ludlam said. “We want to make sure that history here isn’t repeated [concerning soil contamination].”

Chris and Charlie work with junior Courtney Mallard and sophomore Amelia Kinney. They complete surveys about chemicals found in soil and results of their studies have shown concerning levels of toxic metals.

Their findings have accomplished the goal of the program: to have young researchers piece together human impact on soil to show how we have affected the environment.

This research was introduced last year when Mr. Vaillancourt approached Chris about conducting analysis. This year, things are a little more organized, with Chris, Charlie, and Amelia meeting every other day during E period, and Courtney conducting research as an extracurricular.

“The overall goal of this class is to get students involved in real science and their community and if they’re genuinely enthusiastic about it then I’ve accomplishment my goal,” said Mr. Vaillancourt, who considers himself a mentor as much as a teacher.

And that is exactly what he did.

Charlie Lane, Amelia Kinney, and Chris Ludlam were part of AMSA’s presentation team in New Hampshire.

“It’s been fun,” Charlie said simply.

In the big picture, these high school students are conducting research that most of their peers only dream of doing. Many times, these types of research opportunities are available only at the post-graduate level.

“This is an experience that is unique to AMSA,” said Dr. Scott Joray, the science department chair. “We are using a new methodology for teaching high school students college- and graduate-level courses and research opportunities.”

As the youngest research team member, Amelia felt fortunate to get into the program so early. “I’m glad I took this class because now I am better informed about what is in the ground around us,” she said.

Amelia has worked with the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA) to collect soil samples from farms across Massachusetts.

“With urban and organic farming becoming more prevalent it is essential for farmers to know what is in their soil,” Amelia wrote in her abstract that she sent to the Geological Society of America (GSA). She tested the soil for levels of 15 different elements, including lead, arsenic, mercury, titanium, selenium, and chromium.

After finding alarming levels of some of these in the soil, Amelia immediately contacted farm owners. She also included informational packets on actions farmers can take to fix the amount of dangerous elements in their soil, primarily mercury and chromium.

After coming across former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney’s issuance of an Environmental Protection Agency test in 2000 following complaints about the increase of cancer in residents, Charlie was interested in the previously conducted research of the Milham Brook area and wanted to continue it.

Charlie found levels of lead, arsenic, chromium, molybdenum, and mercury that were above acceptable EPA levels. Charlie said that “should the area undergo development, the area could become a potential health hazard to those working to develop the area.”

“Results of this study will initiate future investigations of arsenic and lead migration across the Milham Brook into one of the city of Marlborough’s drinking reservoirs,” Charlie added.

After he conducted his research, Charlie wrote an abstract and sent it to the GSA in December.

Chris did the same after conducting a lead survey across Marlborough.

Courtney Mallard has found toxic levels of mercury and chromium along parts of the Assabet River.

Chris looked for lead levels and what caused them, stating that “due to its history and high traffic volume, Marlborough is a probable candidate for [lead] contamination in the soil primarily through lead paint, leaded gasoline, and lead arsenate pesticides.”

The lead levels varied from background level—or what is in the soil naturally—which is suitable, to above EPA standards for a recreation area.

The EPA standard background level for lead is 400 parts per million in public play areas. Chris found three locations that were above that level: the Marlborough library, the Marlborough airport, and the home of an AMSA family.

“We weren’t surprised based on the background research we completed for the project; however, it’s a major concern that the lead is staying in the soil,” Chris said.

The research opportunity also was offered to AMSA students who wanted to explore soil on their own, outside of taking the course, and Courtney took Mr. Vaillancourt up on it.

Courtney conducted an explorative metals analysis of the Assabet River and researched pollutants from industry and that area.

She found toxic levels of mercury and chromium, which were most likely the results of a leather factory along the Assabet River, and high levels of arsenic and copper which Mr. Vaillancourt said were most likely the remains of a lumber mill.

After the students collected their data, wrote their abstracts, and sent them to the GSA, they were offered the opportunity to present their findings at a conference sponsored by the GSA in Bretton Woods, N.H. from March 23 to March 25.

By working with the GSA, Mr. Vaillancourt hopes it introduced students “to the scientific community” and helped them “gain experience in presenting findings.”

“We want to expand the high school science program and for students to have genuine scientific experiences,” Mr. Vaillancourt said.

Considering what students have found and how they’ve presented that information, it’s probably safe to proclaim the mission accomplished.

If you asked Rebecca’s friends how they would describe her, they would probably say compassionate. She cares a lot about her friends, and always tries...