Flint: A cry for justice for a city in need

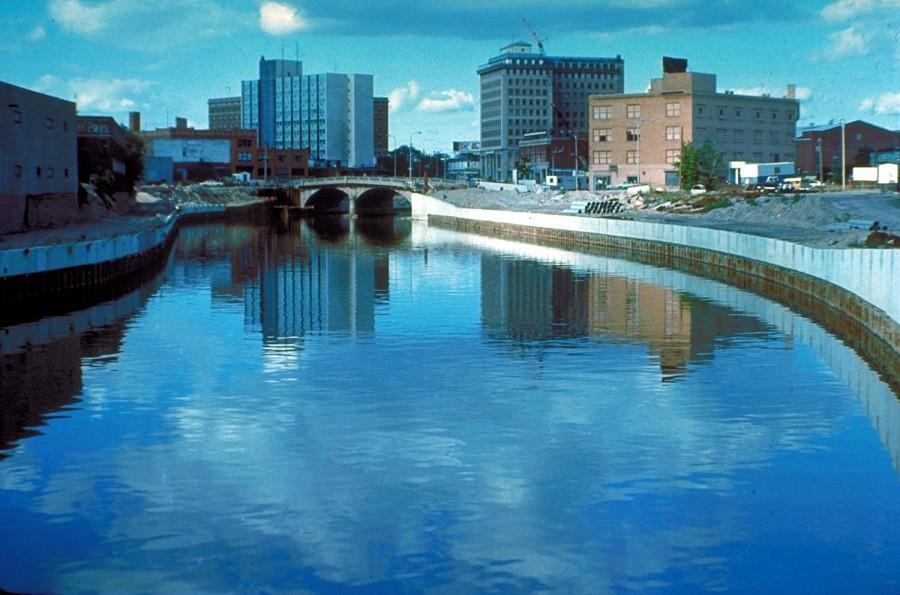

Google images/Creative Commons license

The water supply for Flint, Mich. has been contaminated with lead.

What has happened in Flint, Mich. is an embarrassment.

The entire city of Flint deserves more than the state government has given it, and a simple sorry isn’t going to cut it. State and federal officials need to be held accountable for the gross injustice that has been carried out against the people.

The water supply is contaminated with elevated levels of lead, reflected now in the blood of the city’s children. Lead is extremely toxic and causes developmental problems. It is a crisis, plain and simple.

The outright denial of there being anything wrong with the water in Flint for months despite residents who reported rashes, hair loss, and elevated blood lead levels is worrying. The fact that concerned parents brought bottles of yellow water to state officials, who looked them straight in the eyes and said that nothing was wrong, is sickening.

The root of the problem seems to be that the state of Michigan cared more about the bottom line than its residents’ lives. The change of water sources, from Lake Huron to the Flint River as a cost-cutting measure, was just the beginning of a series of unfortunate events.

The switch of water sources was preceded by a financial crisis in Flint that resulted in the state government taking over and assigning an emergency manager. In order to cut costs, Flint stopped buying the Lake Huron-treated water from Detroit Water and Sewage Department (DWSD) and started taking water from the Flint River in 2014. The switch was meant to be temporary while Flint waited to join the Karegnondi Water Authority in 2016.

The Flint River had been used repeatedly as a dumping site for nearby automobile factories, and on Oct. 13, 2014, General Motors spokesman Tom Wickham announced that the water was so corrosive that GM would no longer use it in its plants because the company feared chloride levels would corrode engine parts.

“Everything we do is focused on our customers,” GM wrote in a media release. “Our decision to switch water sources is about making sure the equipment and the parts we machine in that equipment are at the highest quality levels for our customers who drive our vehicles.”

State authorities have been forced to deliver bottled water to the residents of Flint.

As a result of using such toxic water, and not treating it properly despite knowing that it needed to be treated, the pipes in Flint corroded and leaked lead and iron into the water supply. Amidst complaints about the water, DWSD Director Sue McCormick wrote a letter to Flint officials offering to reconnect them to Detroit’s water supply, to which Flint officials continued to claim that the water was fine.

Not long after the switch to Flint River, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, Director of Pediatric Residency at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, insisted that the city switch back to the Lake Huron water after she released a report in September that found blood lead levels had dramatically increased since the switch.

According to her report, blood lead levels in children aged 5 and younger had nearly doubled after the city switched water sources.

“In some neighborhoods, it actually tripled,” Dr. Hanna-Attisha was quoted as telling CNN. “[In] one specific neighborhood, the percentage of kids with lead poisoning went from about 5 percent to almost 16 percent of the kids that were tested.”

The effects are irreversible. Lead poisoning, especially in young children, damages the brain irreparably. Nearly 7,000 children are reported to have been affected, and that doesn’t include people who visited Flint during its nearly two-year-long poisoning.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, lead at a low dose can impair a child’s IQ, cause children to develop behavioral and learning problems, as well as result in anemia. Professor of Epidemiology Kim N. Dietrich at the University of Cincinnati published research in 2001 that found a correlation between early exposure to lead and juvenile delinquency.

In a community where many of the residents are under the poverty line and already face great challenges, lead poisoning can doom a generation.

All it would have taken to stop this tragedy, according to CNN, is $100 a day, for an anti-corrosive agent that would have prevented roughly 90 percent of Flint’s water problems. Now Flint has to replace its pipes, a project estimated to cost $1.5 billion.

The short-sightedness is amazing. The city had hoped to save $5 million over two years. Now, two years later, the state has to spend 300 times what it had hoped to save in order to fix the problem.

People have called on Gov. Rick Snyder to resign, and perhaps even face criminal prosecution.

What makes this crisis particularly insidious is that the state didn’t deem its residents worth $100 a day.

Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker Michael Moore, a Flint native, has said that Gov. Rick Snyder should be criminally prosecuted.

“When u knowingly poison a black city, u r committing a version of genocide,” Mr. Moore tweeted in December.

In a time when racial politics have come into heightened focus, it is hard to ignore the fact that the state government failed a city of minorities. Although nearly 80 percent of Michigan is white, Flint (population 100,000) is 57 percent African American. About 40 percent live below the poverty line. Fifteen percent of homes are abandoned.

The city does not even have a grocery store.

“Every single obstacle for our children’s success was already here,” Dr. Hanna-Attisha said.

It is hard to believe that race is not a factor in all this.

“While it might not be intentional, there’s this implicit bias against older cities—particularly older cities with poverty (and) majority-minority communities,” U.S. Rep. Dan Kildee, whose 5th congressional district includes Flint, told CNN.

The problem here is lingering questions over what state officials knew and when they knew it.

“These folks are scared and worried about the health impacts and they are basically getting blown off by us (as a state we’re just not sympathizing with their plight),” Dennis Muchmore, chief of staff for Gov. Snyder in 2015, wrote in a July email to the state Department of Health and Human Services.

That was months before officials admitted there was a problem.

It’s time we ask ourselves: If this had been an affluent, mainly white city, would this have happened?

Alyana has always had a passion for keeping up with current events, sharing her opinions and mindset, and contributing to a group effort. Her twin sister...