A split in the vote and a split of opinion

Google image/Creative Commons license

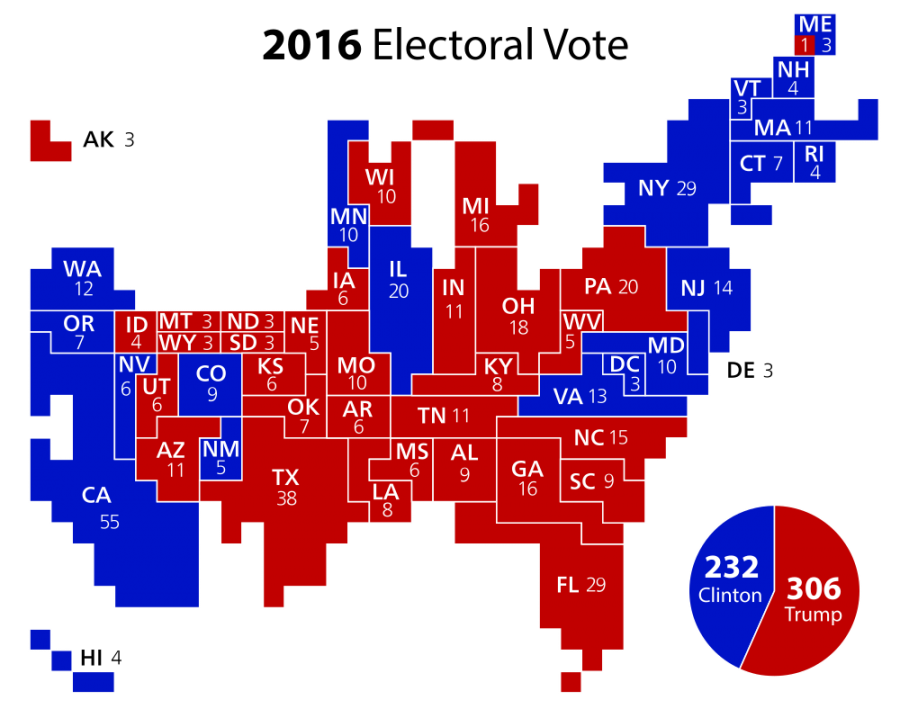

A 2016 electoral map weighted by population.

The Electoral College tally split from the popular vote for only the fifth time in American history on Nov. 8–but for the second time in 16 years–which has led to frustration for many and rage for some.

There were protests in major American cities and on college campuses in the two weeks after the election, with Change.org going so far as to call for individual electors, in an online petition, to vote against their state’s designated winner.

Votes are still being counted, but as of last week, Hillary Clinton has more than a two million-vote national lead over President-elect Donald J. Trump. This is a much larger margin than when George W. Bush won the presidency against Al Gore in 2000–and the largest difference between the popular vote winner and electoral vote winner ever.

A word of caution, however.

“The Electoral College is not meant to be a rubber stamp of the popular vote,” AMSA history teacher Jessica Bowen said. “It often has been, but that’s not what it’s meant to be. There are a lot of good things that the Electoral College does and getting rid of it might produce a lot of unintended consequences that people haven’t thought about.”

The Electoral College was designed to prevent a candidate from winning just one populous region of the country, thereby minimizing the impact of smaller, more rural states.

In the late 18th century, America was extremely regional and states acted more as small united countries. The Electoral College was created so that a candidate had to form coalitions and gain broader support.

“It’s not a democratic system–there are many parts of our government that aren’t democratic and there are benefits to that,” Mrs. Bowen said. “It’s sometimes hard to remember some of the good things that we get from protecting ourselves from [pure] democracy.”

Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein is largely funding a recount in three swing states.

One of those benefits is that smaller states remain relevant in national elections. The time for the Electoral College, however, may have come and gone.

“We need to have a constitutional convention; as a nation I believe we’ve really reached a point where our political system is not working well at all,” said Dr. Anders Lewis, the AMSA history department chair. “What we have in Washington, D.C. is a complete stalemate. I don’t think that’s healthy for a democratic society. We need to find a way to give individual citizens more voice, more power, more influence, and right now we don’t have that.”

Eliminating the Electoral College is not likely in the near future. It would require an amendment to the U.S. Constitution, a long and arduous process with no guarantee of success.

As of now, there is only one feasible way to render the Electoral College irrelevant. Ten states and the District of Columbia have signed The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, in which states pledge to commit their electoral votes to the popular vote winner.

The catch? It won’t go into effect until states with electoral votes totaling 270 (the number required for victory) have pledged. The tally right now is 165.

For this election, the only hope (and it is a faint glimmer at best) for supporters of Mrs. Clinton is that recounts, largely funded by Green Party candidate Jill Stein, somehow flip the results in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania–three states that Mr. Trump won by a combined 100,000 or so votes.

Even if that somehow happened, or that electors decided to collectively go rogue and vote for Mrs. Clinton, she would only have a few weeks before her inauguration to prepare her transition team, which President-elect Trump already has had weeks to do.

A change seems extremely unlikely on every front–for this election and for the near future.

Coretta is a senior and is in her second year writing for The AMSA Voice. Last year she served as the photo editor, and this year finds her as co-editor,...