Race and America: a problem without an apparent end

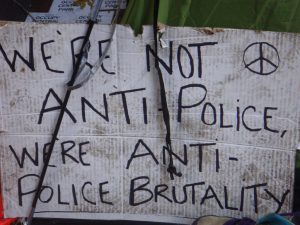

Google image/Creative Commons license

There have been widespread attempts to bring race and violence into the national discussion.

As Barack Obama’s presidency has drawn to a close, his legacy as the first black president is often lauded as a sign that racism is ending in America.

As much as racially symbolic events matter, racism unfortunately extends far beyond the capabilities of one man, even a man of color in such an influential position. Structural oppression, interpersonal discrimination, and the apparent targeting of black Americans, especially by law enforcement personnel, still persist.

Mr. Obama is not really the face of America’s big cities, where minorities face much hardship. He’s an Ivy League graduate, a multi-millionaire, and sometimes regarded as a proponent of respectability politics (which promotes the ideas of marginalized groups policing themselves and that the values of these groups are part of the mainstream, not outside it), which has drawn its share of criticism from across the political spectrum.

His type of rhetoric is largely why white liberals supported his presidency in the first place–his calm, conciliatory assurances seem to absolve them of responsibility.

“There may be times where it is right to be angry and defiant,” said Mr. Obama in an interview with The Atlantic writer Ta-Nehisi Coates on Sept. 27. “And there may be times where you’ve got to give the country and white people the benefit of the doubt.”

When it comes to fatal police encounters, however, activists assert that police have and continue to get the benefit of the doubt seemingly every time.

More than 200 African Americans were fatally shot by police last year. Some of these victims are familiar to us and too many have become household names in the black community: Alton Sterling, Korryn Gaines, Freddie Gray, Philando Castile, Keith Lamont Scott. There are several others whose stories will never be heard and who will never get their day in court.

Police brutality and structural racism are issues that neither Mr. Obama nor any other politician has come close to curing. Reports from The New York Times and the National Association Against Police Brutality confirm that black people are 2.5 times more likely than white people to be shot by police, a considerably high rate considering that they comprise only 13 percent of the American population.

On Sept. 20, Mr. Scott, 43, and a father of seven children, joined the distending list of black people who have been killed by police officers in America in 2016 alone. He was shot by Officer Brentley Vinson in Charlotte, N.C.

Mr. Scott’s family and loved ones had attempted to pursue criminal charges against Officer Vinson, and made a heart-rending case that Mr. Scott was killed recklessly and without any consideration for the importance of preserving life.

Yet, the Scott family and thousands of people across the country who called for Officer Vinson’s conviction were met with disappointment when no charges were brought against him.

In Mr. Scott’s case, the police and local law enforcement once again granted the white officer the “benefit of the doubt.”

“It’s a justified shooting based on the totality of the circumstances,” said Andrew Murray, the district attorney for Mecklenburg County, in a televised statement on Nov. 30. He went on to say that no charges would be brought against Officer Vinson on the grounds of self-defense.

Outcry followed and movements protesting the militarization of police forces continue to gain momentum. Black Lives Matter chapters say that Mr. Murray’s decision gives way to a larger, disturbing pattern within law enforcement.

These black activists describe a fallacy that exists in our perceptions of the black community, which has become normalized to the extent that black lives are expendable.

Charges of excessive violence by police continue to trouble Americans, especially in minority communities.

“Misconceptions and prejudices manufactured and disseminated through various channels such as the media included references to a ‘brute’ image of Black males,” writes Dr. Calvin John Smiley, a sociology scholar from Hunter College of New York. “In the 21st century, this negative imagery of Black males has frequently utilized the negative connotation of the terminology ‘thug.’”

Dr. Smiley went on to note that “[i]n recent years, law enforcement agencies have unreasonably used deadly force on Black males allegedly considered to be ‘suspects’ or ‘persons of interest.’ The exploitation of these often-targeted victims’ criminal records, physical appearances, or misperceived attributes has been used to justify their unlawful deaths.”

These fear-mongering tactics culminate a rationale for racial profiling. Activists like Dr. Smiley argue that blackness has become synonymous with the standard criminal and it becomes convenient to dismiss and thereby acquit those at fault for their deaths.

In Mr. Scott’s case, the district attorney was eager to make the case that he was some sort of menace–a big, scary black man smoking marijuana and pointing a gun at frightened officers. Video evidence and witness testimony, however, apparently show otherwise.

Although Mr. Scott was armed, North Carolina is an open-carry state, which makes it legal to be in possession of a gun.

As the officers on the scene approached Mr. Scott, who was sitting in his SUV at the time, they began banging on the vehicle and attempted to smash the window.

Rakeyia Scott, Mr. Scott’s wife, was filming the encounter and can be heard screaming at the officers that her husband had done nothing wrong. She then went on to say that her husband was suffering from a TBI (traumatic brain injury) and would not do anything to the officers, explaining that he had just taken his medication.

One of the officers, ignoring Mrs. Scott, then shouted: “Drop the gun. Let me get a [expletive] baton over here.”

Mrs. Scott pleaded with her husband, screaming: “Keith, don’t let them break the windows. Come on out of the car!”

Mr. Scott then exited the car with his hands at his sides and no gun visible in any of the video evidence, slowly backing away from the vehicle in a non-combative, compliant manner. Seven seconds later, he was shot dead.

Officer Vinson’s defenders tried to make the case that Mr. Scott was a threat because he did not comply with orders to “drop the gun.”

After he was shot, however, Mrs. Scott said that if the officers had taken a moment to listen to her about his brain injury and took any care to address Mr. Scott’s disabilities, they would have known that Mr. Scott could not have comprehended these orders and was likely in a state of extreme confusion and dissociation.

“He had some issues with his brain,” Vernita Scott Walker, Mr. Scott’s mother, said in an interview with WCSC-TV from her home in James Island, S.C. “It caused him to stutter his words and sometimes he couldn’t remember what he said.”

Also, the district attorney said himself that Mr. Scott never pointed the gun at the officers or made any indication that he would fire his gun at all. Under police regulations, an officer should only use deadly force if his or her life is in imminent danger and there is no feasible alternative.

Officer Vinson, it can be argued, simply took the matter into his own hands. The question of whether Mr. Scott deserved to die because he was a bad person, a convicted felon, or just another dangerous black man is irrelevant.

Based on the prevalence of these assertions in Officer Vinson’s defense, it is clear at the very least that racial inequity exists on multiple levels, in the very fabric of society, despite Mr. Obama having steered this country in a positive direction for race relations.

Black activists still maintain that Mr. Scott deserved respect for his life and justice for his death, as did the 232 others in 2016 who met the same fate at the hands of police officers.

African Americans shouldn’t have to humanize themselves and prove their unequivocal innocence in order for their lives to matter. And right now in America, it sadly seems that not even their deaths do.

Asha is a sophomore and has attended AMSA since the 6th grade. She is a resident of Marlborough and, in her spare time, enjoys running long distance, creative...