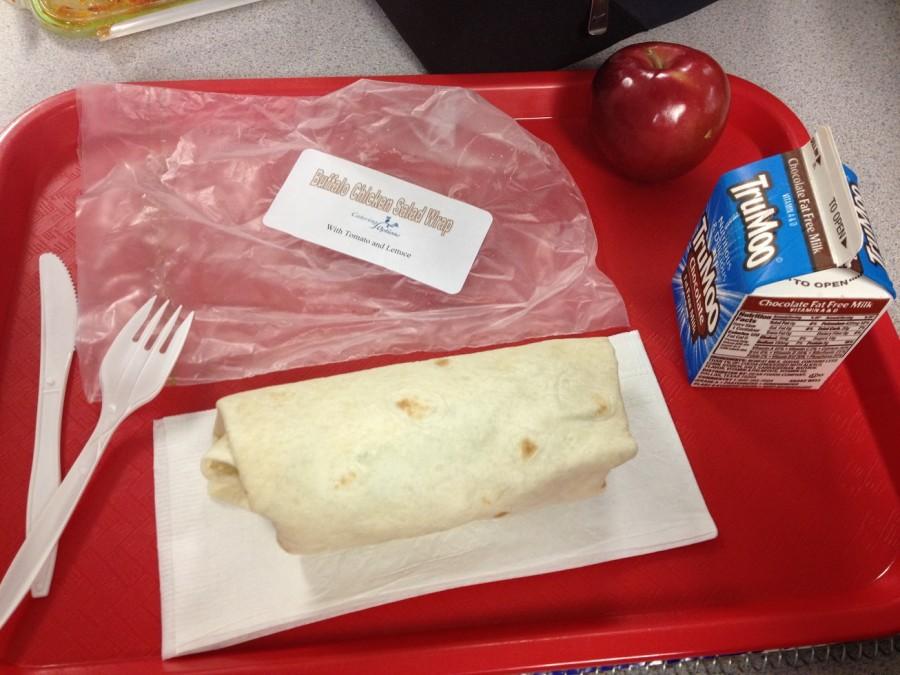

A school lunch evolves and students are a lot happier

Lunch orders and satisfaction levels are up after AMSA switched meal providers.

The scene is the same three times a day, five days a week. The hot and loud lunch room fills with hungry students. They all rush to and from the lunch line in search of a seat next to their friends.

In the past, you could count on most of them looking in disgust at the lunch put on their red trays. Twenty minutes or so later, it wasn’t unusual to see three quarters of that food tossed in the trash.

The gnawing hunger was preferable.

But all that has changed. AMSA switched lunch providers and school lunches are now prepared and served by Catering Options, out of Marlborough.

“[With the former company], when the food got to school, it was cold and not fresh,” said Eileen Hebert, AMSA’s school lunch director.

It was traditional school fare (frozen; processed) served in aluminum trays. Sometimes, it was advertised as one thing but actually was another.

“They whipped white beans and disguised it as mashed potatoes,” Ms. Hebert said. “If you are going to give students food that is cold and not fresh, you should give them at least exactly what the menu says.”

The food now is fresh, hot, and served to students on plates. Most of it ends up in hungry stomachs instead of the garbage bin.

School lunch orders are on the rise—as is the level of satisfaction.

“The parents love the new options,” Ms. Hebert said.

As a bonus, going with Catering Options has provided jobs for locals, since they serve the lunch at AMSA. Some of those workers are college students who gain credit by working with the program.

It would be easy to assume that the change is accompanied by a much higher cost, but that is not the case. Ms. Hebert said that on average the cost of a lunch is only 80 cents higher than last year and that the cost of a large lunch with the former food provider actually cost the school more.

The only complaint is that portions are too small. That is a result of meeting the requirements of the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Program, part of which states that high school lunches cannot exceed 850 calories.

For students who participate in after-school activities, it’s a long time before their evening meal.

“Some of them, I’ve heard, don’t get home until around [10 p.m.] This means that they aren’t eating for a good 10 hours,” Ms. Hebert said.

In an informal poll of 30 students taken during one lunch at the beginning of the month, 13 said they didn’t like the new food options, with most saying that was only because of the portion size and not the quality.

“The quality of the food has improved; however, the serving size of the food is lacking,” sophomore Robert Williams said.

Vending machines at the school have been overhauled to offer healthier choices, but the trick is getting students to buy into the idea that they need to eat better—and perhaps less.

“[Some] students bring large quantities of unhealthy snacks because there isn’t enough food for them to eat,” Ms. Hebert said.

The battle over what and how much teenagers eat isn’t a new issue. What is new is that at least in that loud and hot lunch room, the primary meal is better, more popular, and not going to waste.

It’s a start.

Nick Sousa is a member of the class of 2017. In school, he excels in computer science. Looking forward, he sees himself studying in the field of computer...