The longest government shutdown in the history of the United States ended in November, and there is another one looming at the end of this month, but what does this actually mean?

A shutdown occurs for the simplest of reasons: The government has not provided the means for the country to pay its bills.

The 43-day shutdown that ended on Nov. 12 sounds like an abstraction until you focus on one thing — money. Congress simply didn’t pass the bills needed to keep the lights on.

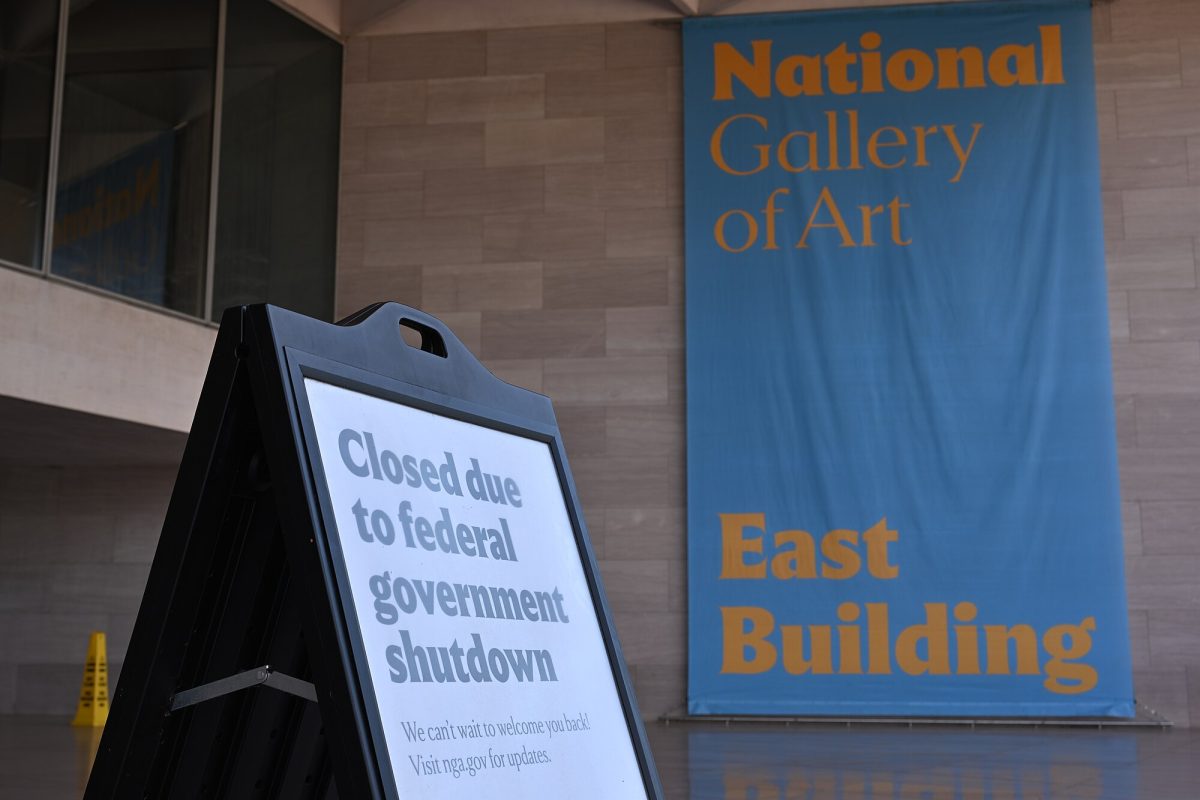

And because it didn’t, hundreds of thousands of workers, airports, museums, agencies, and entire programs were pushed into limbo overnight.

The shutdown began just after midnight on Oct. 1 when Congress failed to pass spending bills or a stopgap measure.

It lasted until President Donald J. Trump signed a compromise funding package. Before that happened, essential functions, such as national security and air traffic control, continued under special authority. Other services paused, including small business loan processing, economic data websites, and many federal museums, parks, and research offices.

This shutdown grew out of a fight over funding the federal government for fiscal year 2026 and whether to extend temporary enhancements to Affordable Care Act (ACA) premium tax credits.

Democrats pushed to tie an extension of those subsidies to any long-term funding bill. Republicans rejected that approach, arguing that health-care policy should not be negotiated during a shutdown.

The prior funding law expired without replacement, triggering the Oct. 1 shutdown.

The House passed H.R. 5371, a stopgap bill drafted by Republicans, but Senate Democrats blocked it, saying it failed to protect ACA subsidies and contained policy changes they opposed.

Throughout October, both chambers tried and failed to pass alternative bills. Senate Democrats offered a compromise reopening the government while extending subsidies for one year, but Senate Republicans declined.

A bipartisan House group floated a two-year extension with limits on eligibility, but it never became the main vehicle.

The White House signaled it would sign a “clean” funding bill that did not include subsidy extensions.

Meanwhile, the effects spread nationwide. Between 750,000 and 900,000 federal workers received no paychecks or were furloughed.

Many turned to savings, food banks, or temporary work. Some states used their own funds to keep food assistance operating, warning they could not sustain that for long.

Airports became a visible symbol of the strain. With FAA and TSA staffing disrupted, travelers faced longer lines, delays, and widespread cancellations.

Science and health agencies saw furloughs and slowed research projects, inspections, and grants.

Some economists estimated the shutdown cost the U.S. economy $7 billion to $14 billion in lost output. Much of that loss came from delayed spending, but some unpaid federal labor will not be recovered.

For many people, the numbers involved in federal budgeting can be difficult to grasp.

“It’s not unusual to have this kind of thing happen, especially now — it’s also not unusual for people to argue over money in general; this happens in everyday life, and on a government level it’s going to be that much more complex,” AMSA history teacher Aaron MacAdams said.

He added, “To use that to try to force or pressure the other side to do something — essentially using the American people who are going to be affected by that as your wedge, as your play — that’s a questionable thing to do, and it’s fairly unusual in the length of it and the specifics, and to do it over, if it’s true, over $1.5 or $1.7 trillion is a pretty big deal — that’s a big political gamble to take.”

Commentators noted that using a shutdown in a fight over health-care subsidies risked normalizing brinkmanship.

Supporters of the Democratic strategy argued that enhanced ACA subsidies are now central to the health-care system and that letting them lapse would raise premiums or push people out of coverage.

Republicans countered that tying health-care policy to government funding would encourage repeated shutdowns.

The turning point came in early November, when Senators from both parties finalized a revised version of H.R. 5371 that acted as a “clean” continuing resolution.

It kept most funding at existing levels through Jan. 30, fully funded several departments for the year, and included targeted exceptions for security and disaster relief.

It did not extend ACA premium tax credits.

Democrats only secured a commitment for future votes.

The bill passed the Senate with bipartisan support and cleared the House largely along party lines. The president signed it on Nov. 12, ending the shutdown.

As operations resume, some effects will fade quickly, but others — missed bills, drained savings, research delays, and backlogs — will take months to unwind.

The central debate over extending ACA subsidies remains unresolved, and another funding standoff is looming.

For now, the 2025 shutdown shows how fights over health care and budgets can ripple outward — from the Capitol to airports, laboratories, classrooms, and households that had no say in the conflict, but felt its impact every day.