Rolling Stone breaks a fundamental rule of journalism

Google image/Creative Commons license

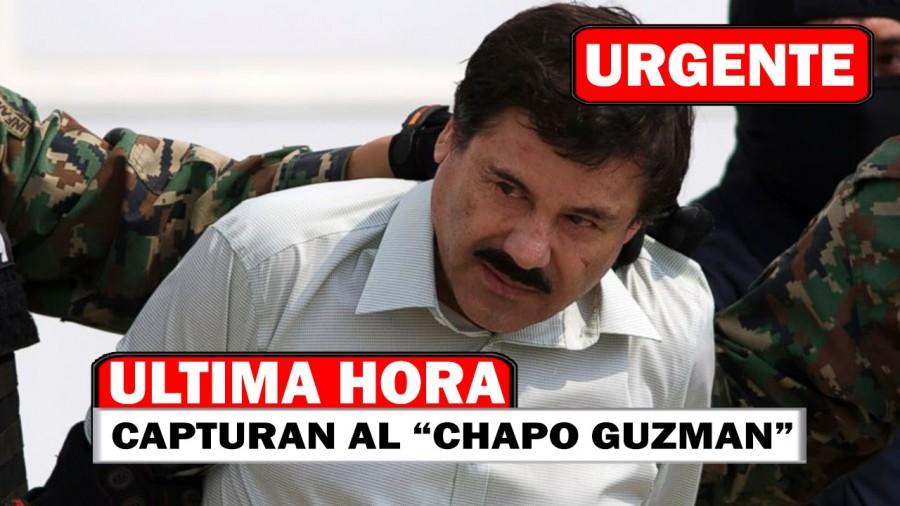

Rolling Stone magazine erred by giving Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman editorial control over a piece about him.

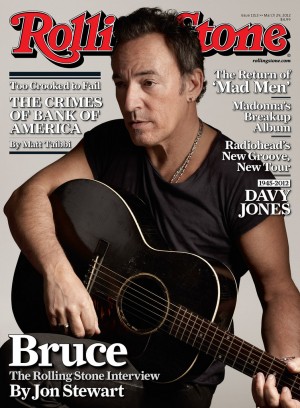

One would hope that you learn from your mistakes—apparently Rolling Stone magazine hasn’t.

Rolling Stone faced much-deserved condemnation after a 2014 piece about an alleged sexual assault on the University of Virginia campus was widely discredited. The magazine retracted the story, titled “A Rape on Campus,” in April after the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism released a report stating that Rolling Stone failed to engage in “basic, even routine journalistic practice.”

The article, riddled with mistakes, broke every rule journalists live by. The magazine relied primarily on a single, anonymous source referred to only as “Jackie”; it did not contact three of her friends quoted (also anonymously) in the piece; it did not identify the alleged victim; and it did not give university officials enough information to adequately respond to questions.

In short, the report stated, most of the problems with the piece could have been avoided had Rolling Stone simply followed basic “reporting pathways.”

Now, nine months after the retraction, Rolling Stone has screwed up again—big time.

The magazine was once a magnet for respected writers, who churned out quality journalism.

On Jan. 9, Rolling Stone published a story about infamous Mexican drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, written by actor Sean Penn. What could have been a great piece of journalism was ruined by Rolling Stone’s lack of responsibility.

Rolling Stone committed one of the deadly sins of journalism—letting the subject of the piece have the power to review and approve the article.

This destroys any legitimacy that the article may have. It was made more complicated by Mr. Guzman’s outlaw status—at the time of the interview he was a wanted man for escaping from a Mexican prison. One certainly wonders if the drug lord, if given the opportunity, could and would have changed anything that may have risked his recapture (which happened anyway, the day before Mr. Penn’s piece was published).

Jann Wenner, the co-founder and publisher of Rolling Stone, tried to defend the magazine’s mistake and was quoted in The New York Times as saying that “I don’t think it was a meaningful thing in the first place. We have let people in the past approve their quotes in interviews.”

The fact of the matter is that any self-respecting journalist who cares about transparency and independent, objective reporting would not have done what Mr. Wenner did.

The New York Times reported that Andrew Seaman, chair of the ethics committee for the Society of Professional Journalists, wrote online that “allowing any source control over a story’s content is inexcusable.”

With Mr. Wenner telling the public that this is not the first time his magazine has let subjects approve stories and content, how can we trust anything that comes from the publication?

Clearly, Mr. Wenner wanted and needed this story to be published. It gained the magazine notoriety. It was a chance to move past the University of Virginia debacle.

But the lasting message here is that Rolling Stone apparently has no regard for following the basic tenets of journalism; instead it spits out stories that will gain revenue and attention.

That makes it a tabloid. What used to be a home for great writers such as Hunter S. Thompson is now just an unreliable joke that seems hopelessly disconnected from actual journalism.

Steven is a senior and has been attending AMSA since 6th grade. He is the resident cartoonist for The AMSA Voice. He has always had an interest in the...